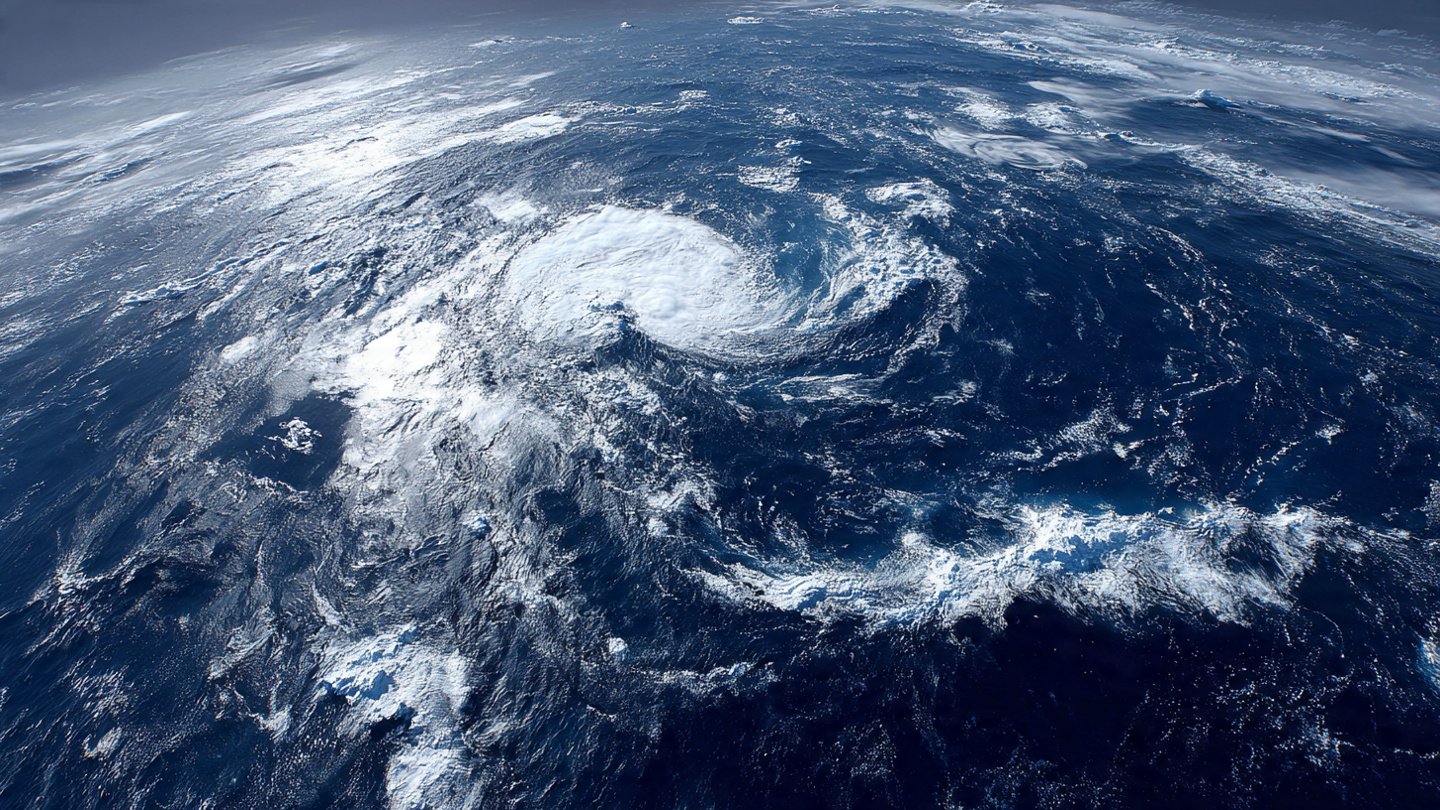

Recent headlines have been alarming: some reports claimed that a major Southern Ocean current has “reversed for the first time in history,” signaling a risk of systemic climate collapse. It’s true that scientists are observing significant changes in the Southern Ocean, but the interpretation of those changes is complex and evolving. This article separates the data, the misinterpretations, and the real implications for the global climate — helping readers understand what’s actually happening and why it matters.

What the Headlines Got Wrong — and Right

Some media reports said a Southern Ocean current had reversed direction and that this threatened a full breakdown of Earth’s climate systems. One such claim was widely circulated online, suggesting a reversal of the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) and even a collapse of the global ocean circulation machine.

However, authoritative fact checks show that no current has been confirmed to have “reversed” direction in the dramatic way described. A recent Newsweek analysis concluded that the scientific paper fueling these claims did not report an outright reversal of ocean currents. Instead, the paper documented unexpected trends in ocean salinity and sea ice, which are important but not proof of a wholesale current switch.

Pinning a reversal on current circulation based on one press report was misleading — much of it stemmed from early press releases that included technical errors or mistranslations.

That said, the Southern Ocean is indeed changing rapidly, and the changes have serious implications for climate dynamics.

What Scientific Studies Have Found

1. Salinity Patterns Have Shifted

New research shows that, after decades of gradual freshening, the surface waters of the Southern Ocean are becoming saltier. This shift in salinity is unexpected because melting Antarctic ice was thought to make the surface layer fresher and more stratified.

When surface water becomes saltier, it becomes denser, weakening the stratification that had slowed the mixing of deep and shallow waters. This can cause deeper, heat‑laden water from the ocean interior to rise, which in turn can accelerate sea‑ice loss from below — a feedback loop that accelerates warming in polar regions.

2. Sea Ice Is Rapidly Declining

Satellite data show dramatic sea‑ice decline in the Southern Ocean — a rate and scale that challenges many existing climate models. The magnitude of sea‑ice loss is comparable to the area of Greenland’s ice sheet, and this decline alters how heat is exchanged between the ocean and atmosphere.

Sea ice plays a critical climate role by reflecting sunlight and insulating ocean heat. Its decline amplifies warming and shifts ocean circulation patterns, potentially affecting weather and ecosystems far from Antarctica.

3. Upper‑Ocean Structure Is Changing

Where once a stable layering kept warm deep waters isolated from the surface, the newer pattern of less stratification allows direct thermal communication between deep and shallow layers. Over time, this can alter not only local climate dynamics but also large‑scale patterns like the thermohaline circulation.

Why Ocean Currents Matter to the Climate System

Ocean currents — especially the major overturning circulations — act like the planet’s heat and carbon transport system.

Global Conveyor Belt: The Overturning Circulation

The Earth’s oceans circulate heat, salt, carbon, and nutrients across the globe through a network of currents known collectively as the meridional overturning circulation (MOC). A well‑known part of this system is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which carries warm surface water northward and colder deep water southward.

While the AMOC is sometimes featured in discussions of climate tipping points — and its slowdown is well documented — scientists have not confirmed a complete collapse yet. But a collapse would have dramatic consequences for regional climates, rainfall patterns, sea levels, and ecosystems.

The Southern Ocean plays a central role in this global overturning, serving as a pathway for water masses exchanging heat and carbon between the world’s ocean basins.

Why Changes in the Southern Ocean Are Significant

1. Climate Regulation and Carbon Uptake

The Southern Ocean covers only about 20–30% of Earth’s ocean surface, yet it plays an outsized role in absorbing both heat and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This filtering capacity helps slow atmospheric warming.

Changes in salinity and mixing alter how the ocean absorbs heat and carbon. If deep heat mixes upward more readily — as the salinity trend suggests — this could reduce the ocean’s long‑term capacity to sequester carbon and regulate temperatures.

2. Sea Ice Feedbacks

Sea ice loss around Antarctica means less sunlight is reflected back to space, a phenomenon known as the albedo effect. Less reflection = more heat absorbed, accelerating warming.

A warmer Southern Ocean also impacts global atmospheric circulation and weather patterns.

3. Ripple Effects on Global Climate Stability

Even without a complete current reversal, significant changes in ocean structure can affect:

- Storm tracks and precipitation patterns

- Marine ecosystems and fisheries

- Coastal sea levels

- Distribution of heat around the globe

The Southern Ocean’s influence reaches well beyond the Antarctic region.

Is the Climate System Near Collapse?

Scientists use the term tipping point to describe thresholds beyond which a system changes rapidly and irreversibly. Crossing one threshold can raise the likelihood of others, a concern highlighted in recent research on climate tipping points. For example, the Global Tipping Points Report 2025 warns that crossing one major threshold increases the risk of cascading changes in other systems — such as ice sheets, ocean circulation, or monsoons.

However, there is no consensus that a global climate system collapse is already underway as of today. The evidence suggests accelerating change and emerging risks, but not an immediate, complete breakdown of overturning circulation systems like the AMOC or global currents.

Where the science is strongest is in showing continued weakening, structural changes, and emergent feedback mechanisms that could destabilize aspects of the climate system if warming continues unchecked.

How Scientists Monitor These Changes

Researchers observe ocean and climate systems through:

- Satellite data — tracking sea ice, surface salinity, and temperature.

- Buoy networks and float probes — measuring deep currents, salinity, and heat content.

- Climate models — simulating future scenarios based on greenhouse gas emissions and ocean responses.

These tools help scientists identify early warning signals and understand complex interactions between the atmosphere, ice, and ocean.

What This Means for Humanity

Changes in ocean circulation and polar processes influence:

Weather Extremes

Altered heat transport can shift jet streams and storm tracks, increasing the severity and frequency of heatwaves, droughts, floods, and cyclones.

Sea Level Rise

Warming oceans expand and ice sheet losses contribute to sea level rise, threatening coastal communities and ecosystems.

Carbon Cycle Dynamics

If oceans absorb less carbon or release stored heat, atmospheric warming could accelerate even if emissions are reduced.

These changes underscore the urgency of emission reductions and climate adaptation planning to reduce the severity of future impacts.

Conclusion: Not Hysteria, But a Call for Science‑Driven Action

The idea that a Southern Ocean current has fully reversed is not supported by peer‑reviewed science; what has been observed is a significant change in salinity and sea‑ice dynamics, with implications for ocean stratification and heat exchange.

These observations are important because they show that the climate system is responding to human‑driven warming in ways that challenge assumptions and models. The risk isn’t a sudden, miraculous reversal of all currents tomorrow — it’s a system increasingly stressed, with emergent feedback loops and greater uncertainty in how stable major components will remain.

Understanding and responding to these changes responsibly — through science, mitigation, and adaptation — is crucial for limiting harmful impacts and building resilience in human and natural systems.